Happy Thanksgiving, all! And I suppose, Happy Black Friday? Even though the UK doesn’t celebrate Thanksgiving, Black Friday has managed to infiltrate its calendar.

[My best friend's aunt lives in London, and we had a hearty Thanksgiving feast!]

I have been pleasantly overwhelmed by the largeness and beauty of London. It is a gorgeous city with seemingly endless traditions (Ever heard why there is a Raven Master - or Beef eaters - in the Tower of London?), historical gems, and amazing architecture.

[The Natural History Museum - filled with many fossils, geological specimens, and third grade classes.]

[Pretty regal Stock Exchange, eh?]

With Twinings tea in hand and a tissue box nearby (I am happily getting over a cold), I am diving into The UK’s, or more appropriately, England’s school dinners.

A short - yet long - history of England’s school lunch program

England has had the longest running school lunch program in Europe, becoming statutory law in the 1940s. However, school meals date back to 1879, where some primary schools in Manchester served free meals to poor children.

The British school lunch program, like the United State’s program, did not emerge from the ethical need to feed children in poverty. While the American program served as an economic stimulus for farmers (check it out in my earlier post here), the British program was created to produce stronger soldiers. Generally, there were significant disparities in health and wellness in England in the 19th century; public infrastructure such as roads, clean water facilities, and access to nutritious foods was wholly inadequate. In 1901, Seebohm Rowntree's survey of working class families in York found that “almost half of the wage-earning population of the city could not afford enough food to keep them 'physically efficient.”'

[Hungry lil' ones in the UK; picture from The National Archives: School Dinners]

As England suited up to fight in the 1899 Boer Wars, the military realized that one-third of all young men were too small or undernourished to serve. Yikes.

[Can you imagine this guy carrying a rifle?]

To solve this military-sized problem, the 1921 Education Act set up the frame for a lunch program and set the eligibility standards for free meals. The government significantly limited the impact of this program, though. Spending limits were set to offset the costs of labor strikes that increased the cost of school lunches, so not all malnourished children received a meal. In 1936, 2.7 percent of school children got free meals.

World War II

While schools lunches only reached 2.7 percent of children in 1936, the Second World War catapulted the program into national importance. With the Boer Wars fiasco in the backdrop, school meals were viewed as fundamental to the health of England’s children, and by extension, future military. School meals became statutory law in the 1944 Education Act (prior to 1944, school meals were allowed but not required) and funding was increased. By 1945, one-third of the entire school population was fed (and 14 percent of meals were free).

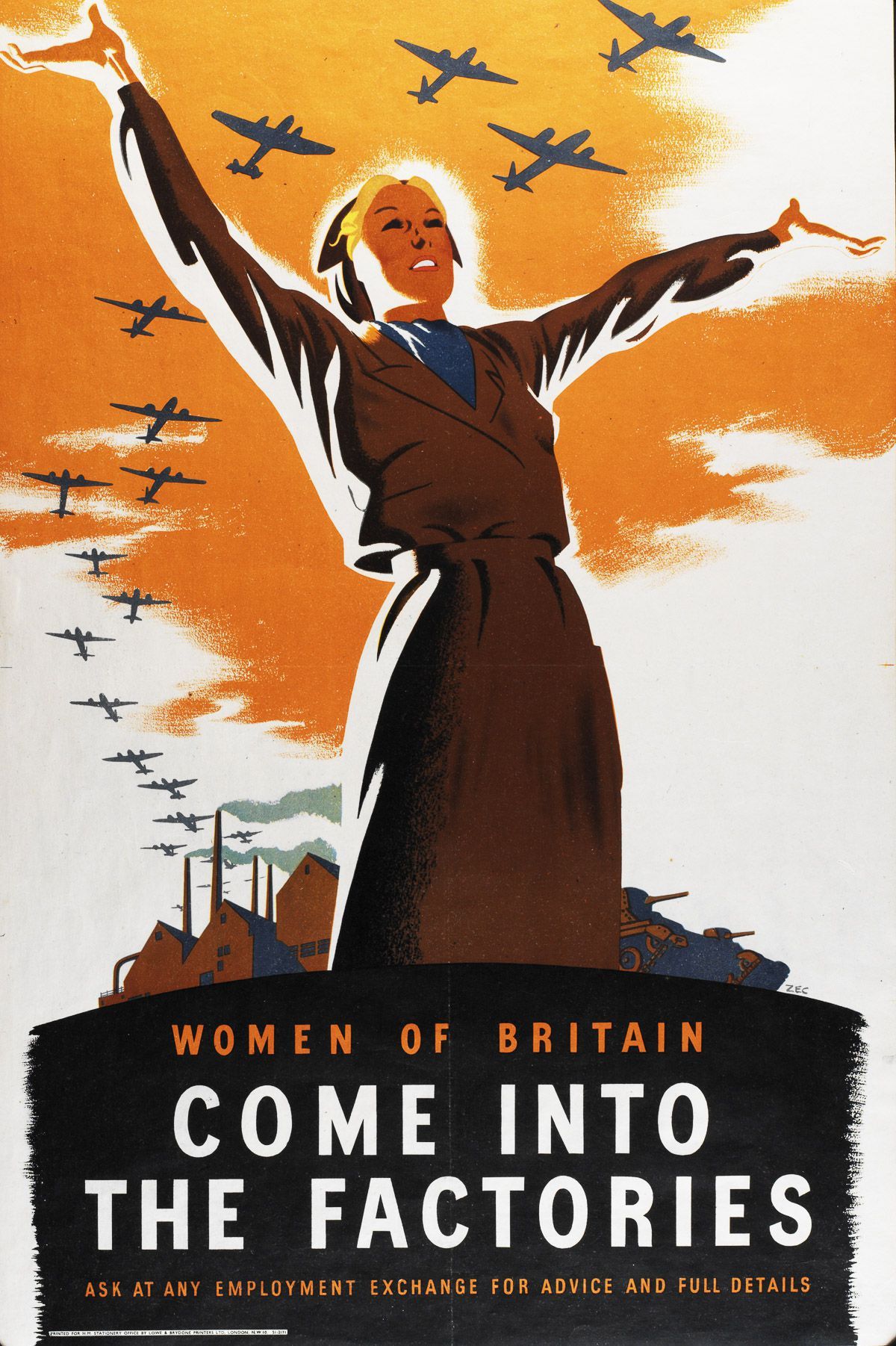

[In addition to "fortifying" their children, another reason for increased access is that women were entering the workforce. Since women were not home to cook, school lunches filled this gap while women filled factories.]

Entering the modern era of school lunches: The rollbacks to the school lunch programs

The school lunch program stayed largely the same until Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative Party came into power. Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in 1979, also elected on the premise that she would cut taxes and decrease government spending. What was the first program to be slashed? The school lunch program and the school milk subsidy, which had provided free milk to all children. Thatcher was labeled as “Thatcher Thatcher, Milk Snatcher!” for her steep cuts in public spending.

The biggest thing impact on the NSLP during the Thatcher administration was the Education Act of 1980, which withdrew the minimum nutrition requirement. This, coupled with hiring private tenders to provide the food, allowed competitive private companies swoop in and sell low-quality, fast food to children. Since there were no nutrition standards, the companies had no impetus to sell wholesome, quality foods.

I cannot explain how impactful this was. Even though there was food rationing in 1950 due to insufficient funding (Hello, WWII!), children in 1950 had healthier diets than children in the 1990s. School lunches were loaded with sugars, salt, and fat while stripping the food of fruits, vegetables, and nutrients necessary for child development.

The nutritional deficiency of school lunches could not have come at a worse time, either! During the 1980s and 90s, technology (TV, computers) became incredibly mainstream, and children became more sedentary. Furthermore, the introduction of the microwave and freezer also led to less home-cooked meals - and more fast food.

Study after study in the 1990s and early 2000s found that children were not getting enough healthy foods in their diets. Obesity doubled from 1980 to 2000. That’s really bad.

Jamie Oliver to save the day!

Jamie Oliver … I think he should be knighted for his important efforts to fix school meals. As I mentioned in my earlier post, Jamie started calling for healthier school meals in the early 2000s. Though it took a TV show, rallying public support, gathering petitions, Jamie succeeded in prompting government action.

And without giving too much away on the contemporary status of the school lunch program (I will talk about that for the next few weeks), school lunches have vastly improved since the 1990s. But where are they now? Stay tuned, that’s coming soon!

[Every day, an artist comes out to create a sand "sculpture!"]

[The Christmas holiday season is underway in London!!]

No comments:

Post a Comment