Hey everyone! I hope you're having as great of a day as my dog, Henry, is! It was National Dog Day yesterday, so I had to post a picture of my #1 fan/friend.

[There are several things I miss about home, but he may be the largest - he doesn't understand Skype!]

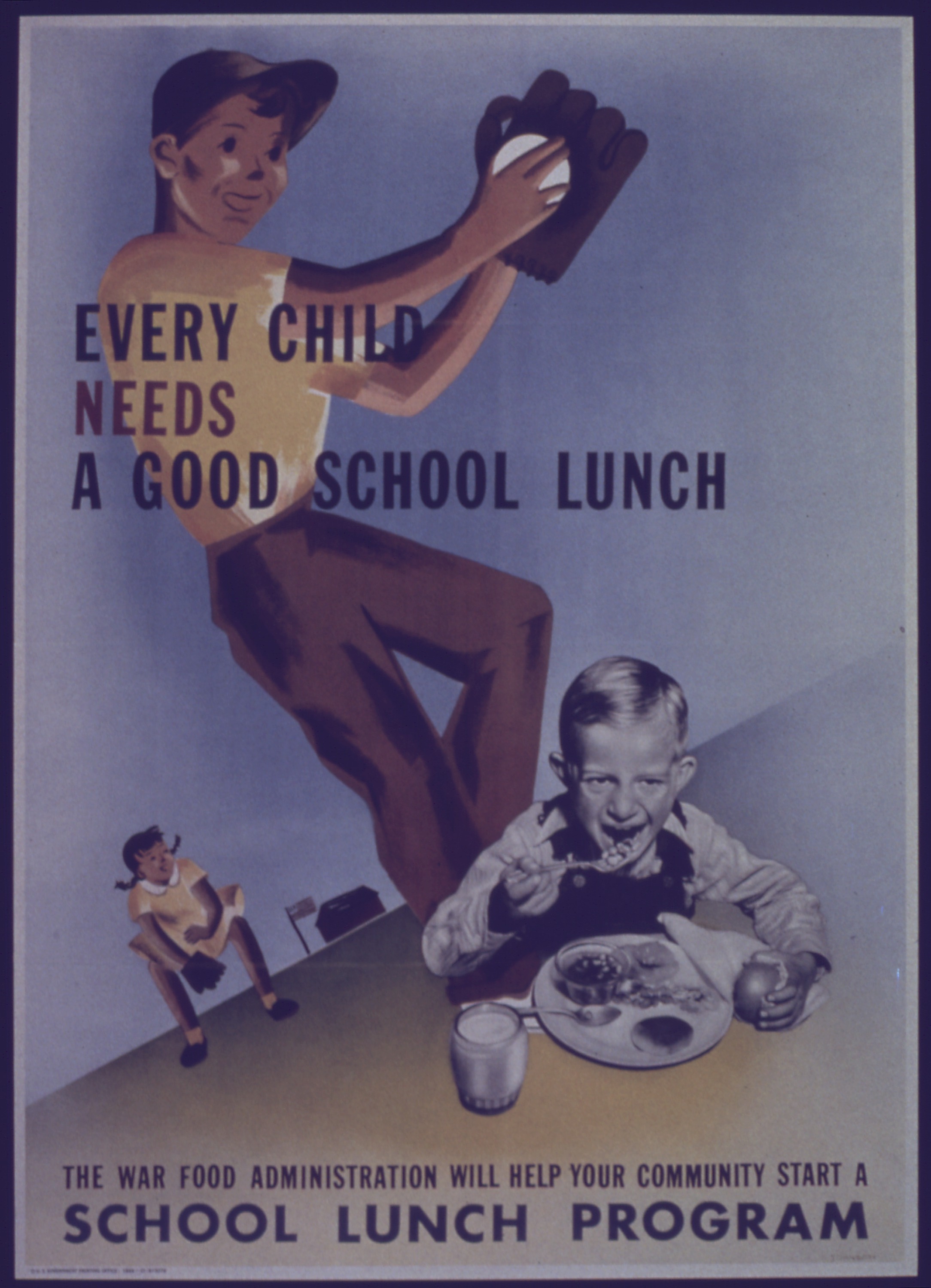

This is the second installment of the "Italian School Lunches and Culture" posts - if you haven't read my first post, check it out here.

When reflecting on the differences and similarities between American and Italian culture as it relates to school lunches, I have narrowed my focus onto two main points - here they are below.

A similarity between programs: Lunches as a rejection of fast/processed food trend

There is an interesting health phenomenon occurring in Italy right now: obesity and overweight rates among adults remain relatively low (around 40 percent, in contrast with America's 68.6 percent), while childhood obesity rates are skyrocketing. Among OECD countries, Italy has the second highest rate of childhood obesity. The International Association for the Study of Obesity show that 36% of boys and 34% of girls aged 5-17 are overweight or

obese in Italy. To contextualize that statistic, the US obesity and overweight rate hovers around 30 percent for boys and girls.

[Worldwide obesity statistics among adults in 2013 ... unfortunately, Italy is not included in this graph.]

This prompts the question, what has created this generational difference in obesity levels in Italy?

Here's a video that provides an answer:

Processed Foods in Italy and America

"Bon appetito, con Coca-Cola." Oh, Coca Cola. Similar to the United States, Italy has been swarmed by the processed industry and its advertising agencies, catalyzing a processed food dependence in the country. In the late 2000s, Coca Cola, McDonald's, and other processed food companies launched intensive ad campaigns in Italy, specifically targeting children. Though there are likely other factors that contributed to Italy's processed food consumption (i.e. women entering the workforce, globalization and urbanization, etc.), the processed food campaigns worked. Over time, the child's diet shifted to energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods; a study showed that "Mediterranean countries were eating about 30 percent more calories by 2002 than they had been 40 years earlier, and these calories included larger amounts of sugar, salt, fat, and refined carbohydrates."

This sounds quite familiar to American readers. The availability of cheap, fast, and processed foods has also significantly contributed to our obesity epidemic.

[Typical supermarket in America: aisles covered with processed foods.]

In the midst of a similar obesity epidemic, the US and Italy have both used their school lunch programs to combat childhood obesity and to lower consumption of processed foods. Indeed, Italy is a little (Okay, a lot) further ahead than the US; back in 2001, the city of Rome passed a regulation that banned processed meals (think of the frozen chicken nuggets or burger patties that are heated up and served) and invested more money into buying locally-sourced, organic foods for school meals. The US is slowly catching up - several policies have been proposed recently that would increase the number of fresh vegetables and fruits while decreasing the amount of simple carbs and sodium. Both of these programs are trying to disrupt the fast-food culture of American and Italian youth, and reestablish a natural, wholesome diet in the youths' lives.

Contrasting School Lunch Options: a Reflection of American individualism

Look at this American lunch line below, and what do you see?

You're probably thinking, "Bananas? ... Fruit? What is there to look at, Erin?"

Well, the answer is options. A child could pick up an apple, a banana, an orange, a fruit cup -

Again, what's the big deal?

In studying the Italian school lunch program, I have learned that the myriad options served in an American lunchroom are not ubiquitous around the world. In Rome, there is a single meal served everyday (my last blog post includes menus if you're curious), nothing else. Obviously, allergies and necessary accommodations are made, but otherwise, you get what you get! Silvana Sari, the School Food Director of Rome in 2011 - who was credited with the massive overhaul of school lunches - said that she didn't agree that students needed to have so many options: "Abroad they ask me, why can't your children choose? They think it's a democratic right to have choice."

This surprised me; is America known for prioritizing choice? My personal observations have affirmed this while in Finland, I have noticed that restaurants offer much fewer options than American restaurants, coffee shops have fewer "flavors" ... And when I looked back at the American lunch menu, I realized that there were multiple choices for lunch everyday - but is this truly a reflection of America's culture?

Academia would say "yes!" Americans value choice - we love options, and often associate a plethora of options with freedom. Barry Schwartz, professor of social theory and social change at Swarthmore College, found that "personal and religious freedom became irrevocably tied to economic freedom from the monarchy and early capitalism" (TED). Personal autonomy - the right to be an individual and have individual rights - bled into the economic sector, predisposing Americans to expect choices in almost every situation (and lots of them!).

[Barry Schwartz, giving his TED Talk - it's a fascinating talk, give it a watch here.]

Though it may seem like normal for school lunch programs to offer choices, could you imagine the converse? "Only grilled chicken for lunch? But my child doesn't like chicken." In Italy, the response would be, "Sorry, that's what is on the menu." I doubt an American parent would stand for this :)

To a certain extent, the amount of choice in the American National School Lunch Program stems from the values that America is known for: individual liberty and choice.

What do you think? Do you see the connection between American values and the lunch program? What does that say about Italian democracy, if so? So many questions, not enough time to answer them in!

Kiitos ("Thanks!" in Finnish) for reading, I am ever so grateful for your support and curiosity.

Best,

Erin

.jpg)